This blog, plus additional exclusive content, was published last Friday on my free Mobility Matters newsletter. You can sign up for the newsletter by clicking here.

In all of the years where I have worked on transport strategies and visions, I have come to realise one thing. The visions we set are as much a commentary on the present as they are a view of the future.

Take the 1960s for example. With the Second World War fading into memory, and reconstruction continuing apace, visions of the future were packed with techno-optimism. There was almost a confidence and swagger about how much we controlled our destiny. About how the aspects of human existence could be broken down into numbers and technology, and designed for efficiency.

Today, we look back on such visions with a wry smile. How silly we were to think all of that. Where are our flying cars and nuclear powered trains? Its obvious now that we couldn’t measure or engineer our way out of social issues – what were we thinking?

Yet, certainly when it comes to how we planned cities and places, I feel that we judge too harshly and too quickly. While according to our modern standards many of the New Towns are “failures,” according to the visions of the time, when you look at from the perspective of the time, a vastly different view comes over you.

In the lexicon of British urbanism, Milton Keynes has long occupied a peculiar space. It is the punchline to a thousand jokes about concrete cows and roundabouts. It’s often dismissed by the metropolitan elite as a “soulless” cultural desert. Yet, if we strip away the aesthetic snobbery and view the city through a strictly rationalist lens—judging it not by how “quaint” it feels, but by how effectively it functions—a different picture emerges.

I live in a small town 10 miles from Milton Keynes, and I visit the city most weeks. When I first moved to the area 22 years ago, I felt the same way many others do about the place. I thought it was a stupid place. Its layout made no sense, it was awful if you wanted to walk or cycle anywhere, and it was clearly designed by an American.

But over the years I have come to realise something. From a standpoint of pure logistics, engineering, and human mobility, Milton Keynes is not a failure. It is perhaps the most successful experiment in vision-led transport planning the United Kingdom has seen in the last 60 years.

For decades, we have been told that the “Garden City” ideal was a romantic notion. But Milton Keynes applied a ruthless, mathematical logic to that romance. It promised freedom and choice, and unlike almost any other city in Europe, it delivered it.

To quote the Original Plan for Milton Keynes:

“The city should offer to its newcomers and its inhabitants the greatest possible range of opportunities in education, work, housing, recreation, health care and all other activities and services.”

To understand my point more, you need to get into the mindset prevalent in the planners and engineers of the time. That of rationalism. The rationalist does not care about the “urban tension” of a crowded street or the “vibrancy” of a traffic jam. The rationalist cares about friction.

For any of you who remember your GCSE Physics class, you know that friction is waste. It is heat, noise, and lost energy. In urban terms, friction is congestion, delay, and unpredictability. A rational transport network is one that minimises friction, allowing economic agents (people and goods) to move from Origin A to Destination B with the highest possible reliability and speed.

If you apply this metric, every single British city is a failure. Your classic British city is radio-centric. The majority of the activity is funnelled into a confined medieval core whose street layout was devised at the time of the horse and cart. The result – friction – is inevitable. Buses get stuck behind delivery vans, cyclists are squeezed into the gutter, and cars sit idling behind the tailpipe of another.

In Milton Keynes, planners sought another way.

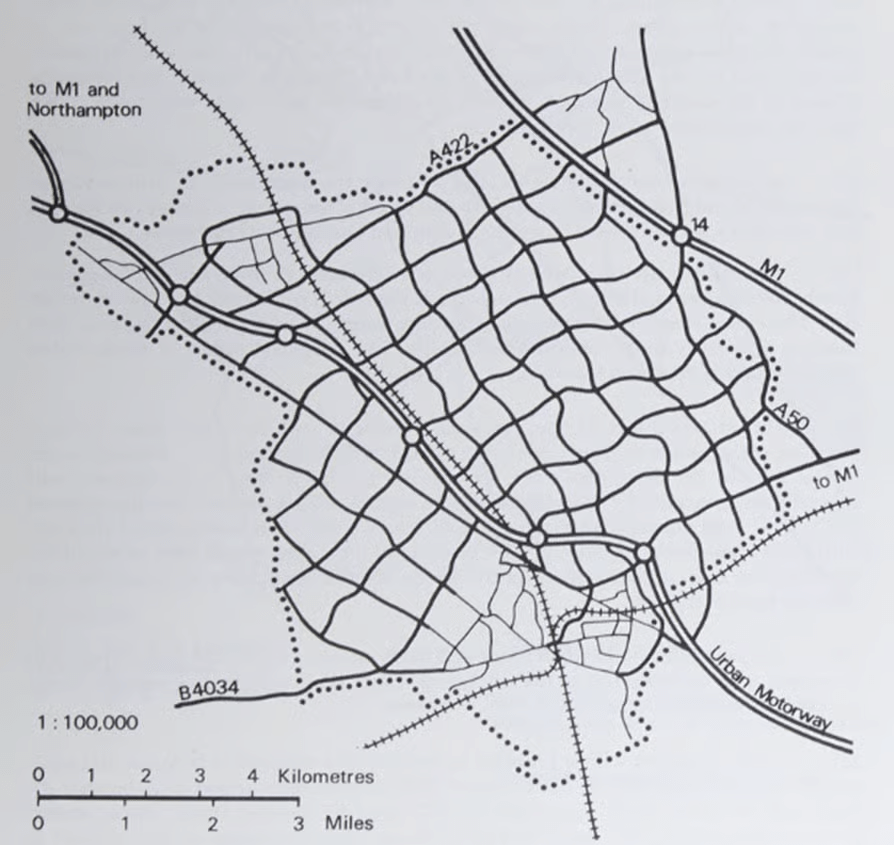

The 1970 Master Plan, drafted by Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker & Bor, was not an evolution of the past – it was a break from it. They designed a grid of roughly 1km squares bound by roads. We know it today as the Grid Road system, and it is probably the most effective highway system in any British city. Where the friction of daily life is engineered out of existence.

The sketch of the main road network in The Plan for Milton Keynes

We often hear about Vision-Led Transport Planning (VLTP) today. It is the trendy methodology of the 2020s, championed by bodies like Transport for London and the Royal Town Planning Institute. The core tenet of VLTP is simple. Instead of “Predict and Provide” (predicting traffic growth and building more roads), planners should “Decide and Provide” (decide what the city should look like, and build infrastructure to force that outcome).

What we mean in reality by VLTP, whether we want to admit it or not, is no more cars. Or at least no more additional capacity for cars, and removing it where we can. The logic goes: “We envision a walking city, therefore we will close roads.”

Milton Keynes is often considered an example of Predict and Provide. Yet, while it was designed and built at a time where Predict and Provide was orthodoxy, in the last 20 years where I have been researching how the transport network of the city was constructed, I have not seen any evidence that this was the case. Yes, the planners did model the likely impacts of development patterns across the city and the consequent traffic movements. But all the time, the vision of the city drove the planning of its transport system. It was very much vision led.

This means that Milton Keynes represents the most aggressive and successful application of VLTP of the last 60 years. Its just not a vision we are accustomed to. The 1970 vision was “Freedom of Movement.” The planners decided that the future citizen should be able to travel anywhere in the city, at any time, without delay.

“To provide for genuine freedom of choice it is vital that journeys should equally convenient in all directions across the city from every home, and the public transport and road systems are intended to achieve this.”

They envisioned a city where the car was not a demon, but a liberator, and where the pedestrian was safe because they never had to compete with a bumper. They saw a vision where personal liberty (I.e. high use of the car) dominated, and they purposely chose it.

Critics call it “car-centric.” A rationalist calls it “delivery-focused.” The city set a performance metric—unimpeded mobility—and fifty years later, it is still hitting those targets in a way that London or Manchester can only dream of.

Consider the experience of the average driver. In most UK cities, the “rush hour” is a period of paralysis. In Milton Keynes, rush hour is merely a period of slightly increased volume. The grid system disperses traffic rather than concentrating it. There are no “arteries” to clog because every road is an artery. The only traffic that does happen is traffic on the routes into Milton Keynes, rather than within.

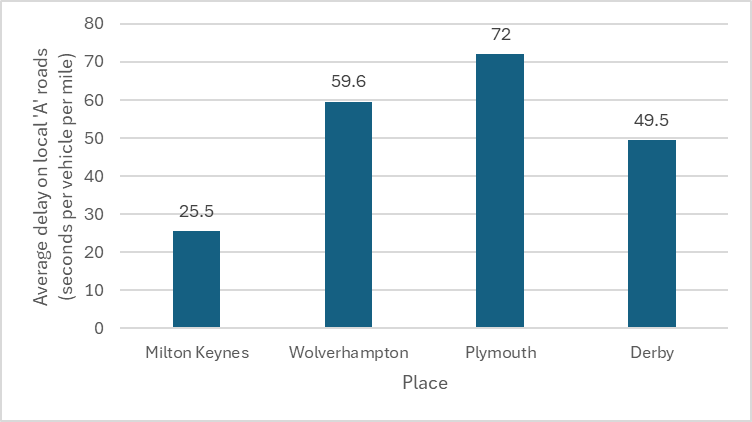

The rationalist looks at this data and sees a victory. While a driver in Plymouth might lose 72 seconds per mile to traffic, the driver in Milton Keynes glides through. This is not just convenience – it is economic efficiency. It is time returned to the people living there—time not spent fuming at a red light, but spent working, resting, or being with family.

You might get the impression in this post that I am being very much pro-car, and that Milton Keynes being pro-car is an unashamedly good thing. My views on cars do not even come close to this, but I do this with the purpose of bringing attention to the elephant in the room. In 2026, it is fashionable to view the car as an inherent evil. But this was never always the case. In the 1960s when the plans for the city were being drawn up, the rationalist viewed the car as a tool. It offers point-to-point, on-demand, weather-proof, private transport. It is, objectively, a highly attractive mode of travel. While the percentage of households owning a car was still only at 40% in the late 1960s, it was on a clear upward trend, reflecting its attractiveness.

The failure of the car in other cities is not the fault of the car itself necessarily. Cars fail in cities when they are forced into spaces not really designed for them, or the demand is stimulated to such a degree that city streets get overwhelmed.

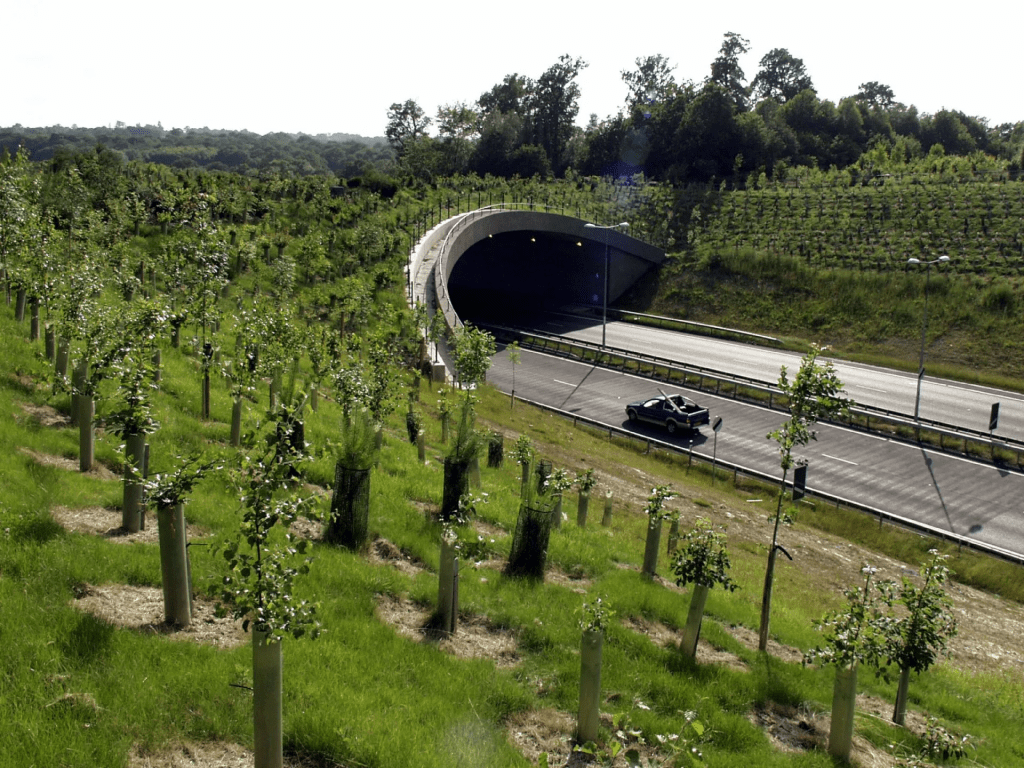

Milton Keynes succeeds in part because it respects the geometry of the automobile. The grid roads (H and V roads) are designed for 60-70mph speeds. The roundabouts allow for continuous flow. Houses are set back behind earth embankments and tree lines to mitigate noise.

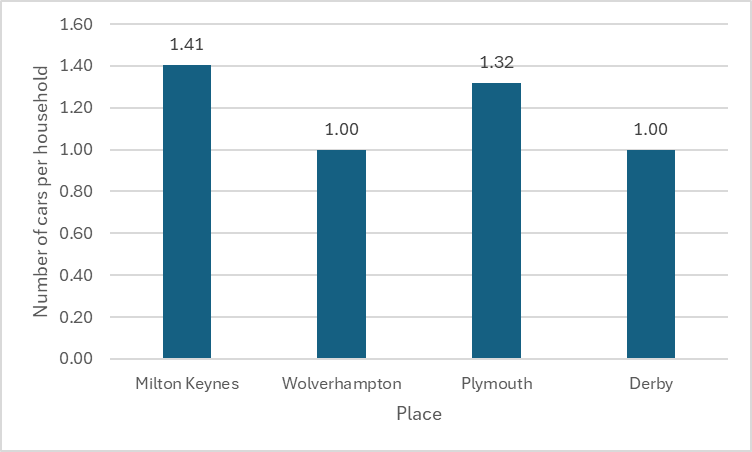

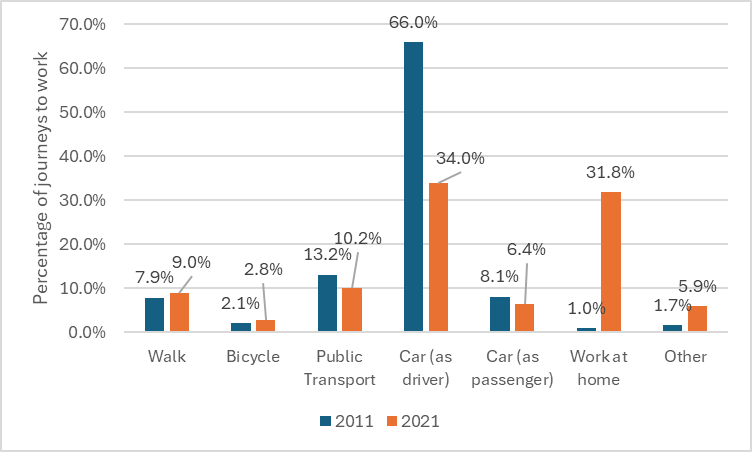

The result is a population that votes with its wheels. It is a city designed for car ownership, and with the intention that people will own cars.

Number of cars per household of Milton Keynes and similarly-sized cities in the UK (Source: 2021 Census – note that official statistics on number of registered cars in local authority areas was not used as Milton Keynes is the registered address of many fleet car companies, thus skewing the data)

Critics argue this creates dependency and it does. But the rationalist argues it creates utility. If the infrastructure makes driving the most efficient choice, rational actors will drive. The triumph of MK is that it accommodates this high level of ownership without the gridlock that usually accompanies it. It proves that mass car ownership can be sustainable on a local level, provided you build the highway network for it. MK had that blank canvass, and made good use of it.

For public transport there is a paradox, and the area where the rationalist defense faces its stiffest test. If you build a city where driving is effortless, why would anyone take the bus?

The “Vision-Led” goal of MK was freedom. By making the car so effective, the planners inadvertently set a lethally high bar for public transport. In a city like London, the bus competes with a Tube system (crowded) or a car (stuck in traffic). In MK, the bus competes with a car that can cross an entire city of 350,000 people in just 12 minutes. The planners themselves even acknowledged that public transport will primarily be for those who do not own cars.

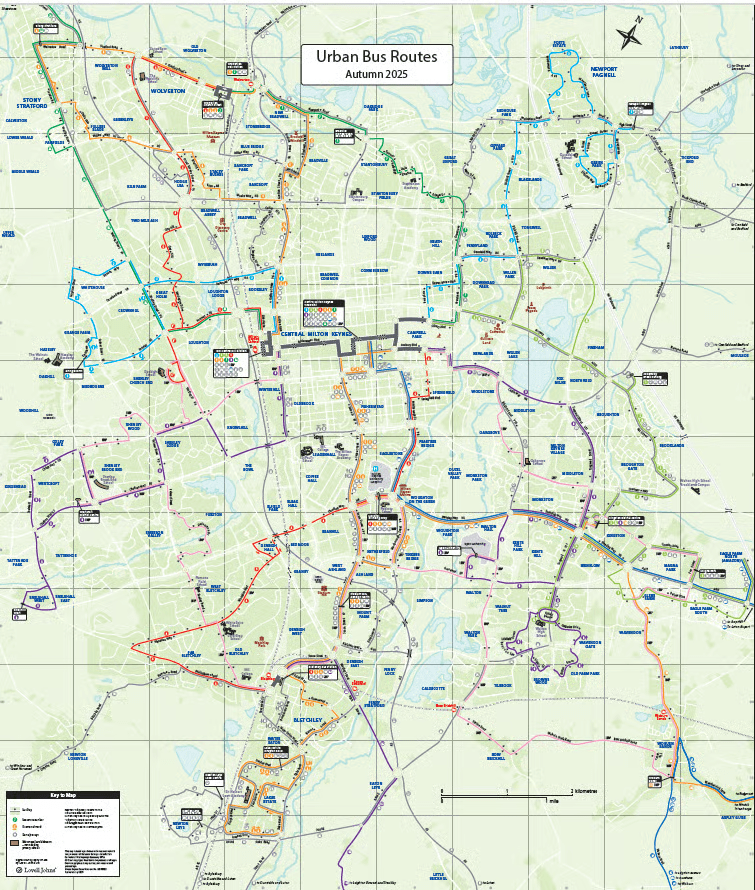

The current urban bus routes in Milton Keynes (Source: Milton Keynes Council)

However, even here, the rational planning shines through in unexpected ways. Because the roads are clear, the buses that do run are exceptionally reliable. 78% of buses in Milton Keynes ran on time during 2025, and while that is comparable to the national average, what brings down that number is the poor reliability of interurban services to places such as Bedford (on the X5 route), Oxford (also X5), Northampton (X6 and 33/X33), Aylesbury (150), and Luton (X1 and MK1). They tend not to get held up within the city. In a twist of irony, the Grid Roads that make it so easy to drive also make MK’s buses among the most reliable in the country.

The rationalist admits that MK is difficult for commercial bus operators. The low density means fewer passengers per mile. But this is a trade-off, not a failure. The city chose space and speed over the density required for high-frequency mass transit. It was a calculated decision.

Perhaps the most frustrating irony of Milton Keynes is that it possesses the finest cycling infrastructure in the UK, yet is often cited as a bad place to cycle. The “Redway” system—over 200 miles of shared-use paths—is a masterpiece of segregation. In London, cyclists fight for survival against lorries. In MK, a cyclist can travel from one side of the city to the other without ever touching a road.

As someone who has ridden the Redways a number of times, they are generally a joy. Mostly smooth surfaces and segregated from traffic, and while the interfaces with cars are far from Dutch standard (and the quality of routes in the Centre is very bad), its far from an awful experience.

But, to the shock of nobody, cycling numbers in the city are low.

Why are the cycling numbers low if the network is so good? The rational choice theory returns. The Redways are safe, but they are often circuitous (to go under/over grid roads) and less direct than the grid roads themselves.

Meanwhile, the car is faster. It takes 16 minutes to drive from Newport Pagnell on one side of the city, to Bletchley on the other, in rush hour. Compare that to the 30 minutes it takes to drive from Perton in Wolverhampton – a city of a similar size to Milton Keynes – to Wednesford Park on the other side of the city.

The infrastructure is a triumph of safety engineering, even if the mode share is a disappointment of social engineering. The rationalist applauds the capacity and the safety, noting that the potential for a cycling boom is built into the concrete, waiting only for the arrival of e-bikes to shrink the distances.

Finally, we look at Central Milton Keynes, or CMK. In a normal city, the centre is the point of maximum congestion. In MK, the centre is a grid within a grid.

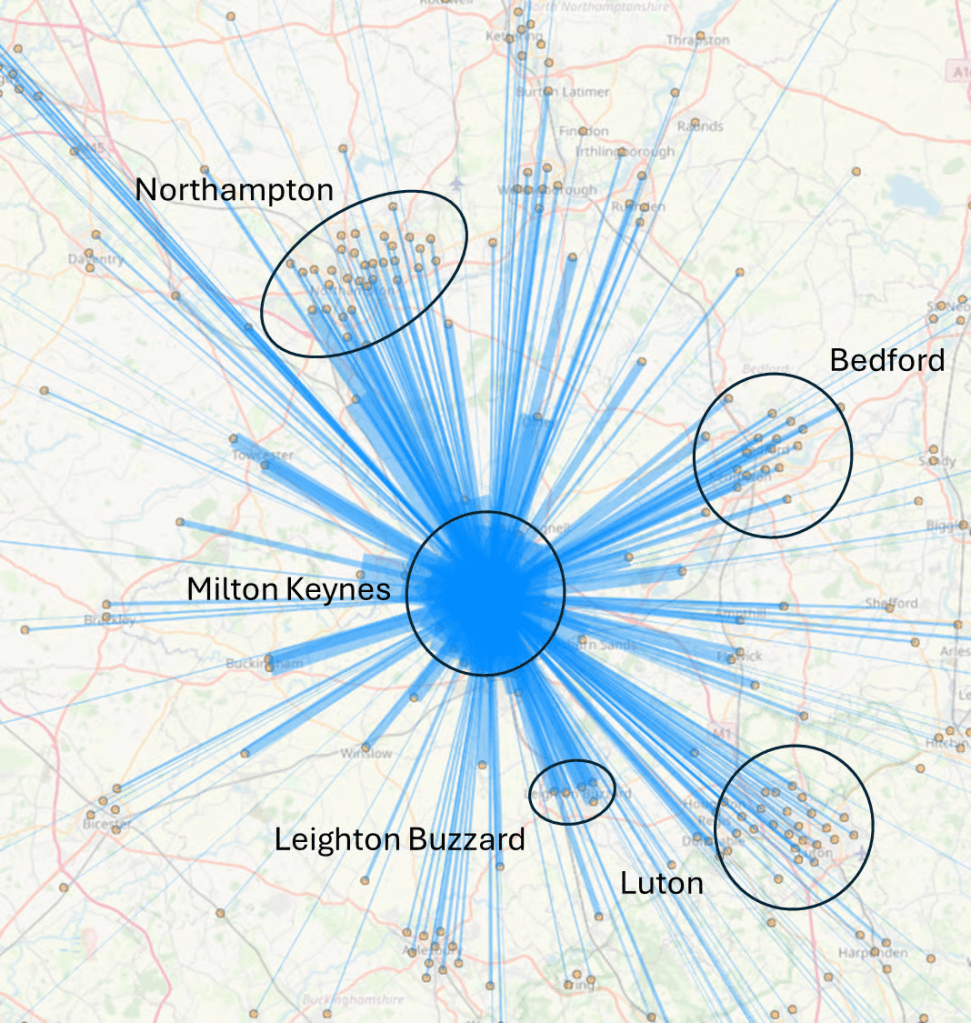

The boulevards of CMK are vast. The parking is ample. It challenges the very notion of a “High Street.” It is a machine for commerce. The “Vision-Led” aspect here was to prevent the strangulation of the commercial core. By ensuring that thousands of workers could drive into the centre, park, and leave without causing a bottleneck, MK secured its economic viability.

While modern urbanists crave walkability and street life, the rationalist observes that CMK functions as a regional economic hub with ruthless efficiency. It draws labour and capital from a massive catchment area because it is accessible. You may say that this is a result of its size – it’s a city of 250,000 after all – but with several medium-to-large sized towns within a reasonable travel time (Oxford, Northampton, Bedford, Bicester, Aylesbury, Luton, Leighton Buzzard, and Rugby to name a few), its success was not nailed-on.

Milton Keynes is a controversial triumph. It offends the aesthetic sensibilities of those who love winding medieval alleys and bustling pavements. It angers the environmentalist who wishes to see the car abolished.

But if we judge transport planning by its ability to facilitate movement, to reduce wasted time, and to separate vulnerable users from heavy metal, MK is a peerless success.

It serves as a provocative case study for Vision-Led Transport Planning. It reminds us that a “vision” does not always have to be about restriction. The founders of Milton Keynes had a vision of optimism—a belief that technology (the car) and nature (the forest city) could coexist in a grid of perfect flow.

They built it. And fifty years later, while the rest of the UK sits in a traffic jam, Milton Keynes is still moving. That is the rationalist’s vindication.

As for me, I do feel that criticizing Milton Keynes without taking the time to understand the original vision only reveals half the story to you. But similarly, if you try and judge it purely on the numbers you miss something more fundamentally important about the quality of the places we live in.

They need life. They need community. They need a sense of belonging. Milton Keynes is an efficient, relentless machine. It is absolutely brilliant at it. But is that enough for a good life? Clearly for some it is. 250,000 people call it home, and I bet most of them are happy with it.

For me its not. But Milton Keynes shows it is possible to be against current orthodoxy, and still deliver Vision-Led Transport Planning. A vision that you don’t like is just as valid as a vision that you do.