This blog, plus additional exclusive content, was published last Friday on my free Mobility Matters newsletter. You can sign up for the newsletter by clicking here.

Charging for road use seems to be having its time in the sun at the moment. Here in the UK, the Oxford Temporary Congestion Charge has come into effect, and the Government is committed to introducing road user charging for electric vehicles. Meanwhile, across the other side of the pond, New York’s Congestion Charge has been making headlines for its traffic reduction powers.

The financial management of urban road networks is undergoing a bit of a transformation. As cities grapple with the dual pressures of climate targets and crumbling infrastructure, the implementation of road user charging may, finally, have moved from a theoretical economic concept to a key weapon in the traffic-busting arsenal. However, as the data from the last two decades demonstrates, the success of these schemes is not merely measured by the reduction in vehicle kilometres, but by something more boring: are they successful financially?

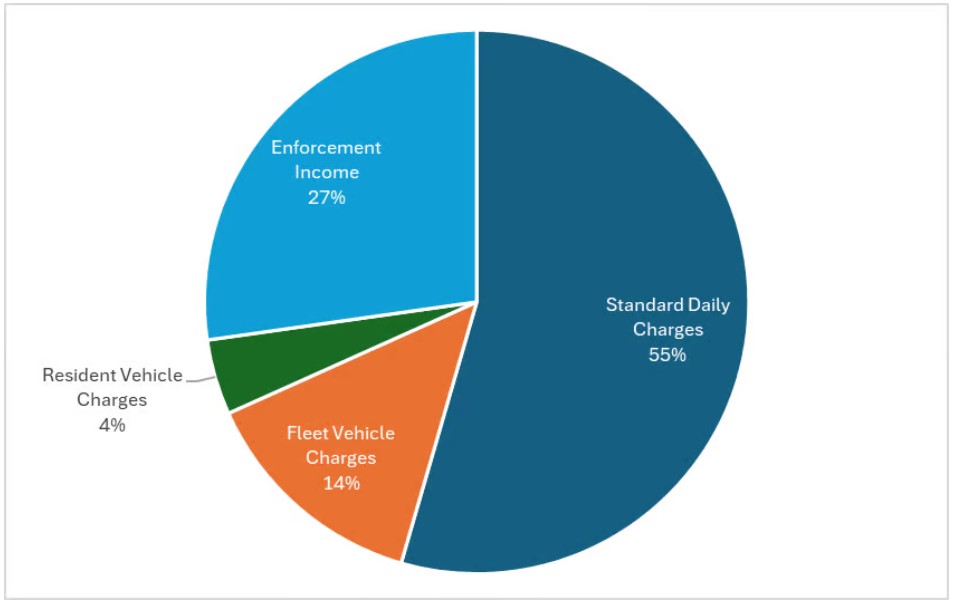

One of the first things to understand about road user charging is that there is no single financial model. Instead, there is a patchwork of mechanisms that behave in radically different ways. On one hand, there is the traditional congestion charge, such as the one seen in London since 2003. This is essentially a daily entry fee, a blunt instrument designed to discourage any vehicle from entering a zone during peak hours. But the revenue model shows a surprising mix of income streams. While detailed data on revenue sources is no longer provided, in 2007/08, Penalty Charge Notices accounted for 27% of revenues.

Sources of income from the London Congestion Charging Zone 2007/08 (Source: Transport for London)

The revenue here is a mix of the daily fees paid by compliant drivers and the much larger penalty charge notices (PCNs) issued to those who fail to pay. In the early years of the London scheme, it was actually the penalties that provided a surprising and significant chunk of the income, making up nearly 33 percent of the gross receipts at one point. This highlights a strange reality where the financial health of a scheme can sometimes depend on people getting the rules wrong.

Contrast this with the Nottingham Workplace Parking Levy (WPL). This is not a charge on the act of driving itself but rather a levy on the destination. It targets employers who provide more than ten parking spaces for their staff. From a financial perspective, this model is remarkably stable. Because the council is dealing with a fixed number of known businesses rather than thousands of transient motorists, compliance is nearly 100 percent. There are no cameras chasing individual cars and very few penalty notices. Instead, there is a predictable, annual stream of income. Between 2012 and 2022, Nottingham generated over £90 million in revenue, which allowed the city to leverage over £1 billion in external funding for its tram network and electric bus fleet. It is a slow and steady model that lacks the in-your-face style of paying a daily fee in London, but offers much greater long-term certainty for the Council.

In Milan, the transition from the Ecopass to Area C shows yet more variation in the charging models. The Ecopass, introduced in 2008, was a pollution-based charge that varied from €0 to €10 depending on the vehicle’s engine. When the city shifted to the Area C flat-rate congestion charge in 2012, revenue increased from approximately €12 million to over €20 million in a single year. By 2018, annual income had risen to €33 million. Milan’s model is particularly transparent about its reinvestment: 62 percent of net earnings are dedicated to strengthening public transport, 22 percent to sustainable mobility projects, and only 16 percent to operating costs. This level of granular financial reporting is essential for maintaining the public trust necessary to sustain such a scheme.

When a local authority proposes a charging scheme, the financial forecasts are always scrutinised with intense suspicion. There is sometimes an assumption that councils are overestimating potential revenues to justify the political pain of the charge. However, the history of these schemes suggests that the opposite is true. The projects that succeed are those that embrace deeply conservative, almost pessimistic, revenue forecasting.

The London Congestion Charge provides a classic case study in this regard. Before the scheme launched, planners were cautious. They predicted a net annual revenue of somewhere between £130 million and £145 million. When the scheme actually went live, the traffic reduction was much greater than they had dared to hope. While this was a massive win for congestion, it meant that fewer people were paying the daily charge than anticipated. If the planners had been aggressive in their revenue targets, the scheme might have been viewed as a financial failure in its first year. Because they were prudent, they were able to beat the forecasts and invest more money in improving buses and cycling in the city.

We see a similar pattern in Stockholm. During the 2006 trial, the traffic reduction across the cordon was approximately 20 percent, which was at the high end of expectations. In terms of predictive accuracy, the Swedish models were remarkably precise for peak-time travel, where they predicted an 11 percent reduction and observed 12 percent. However, they significantly under-predicted the reduction in off-peak travel. Those who favour the conservative approach in forecasting tend to win out because they build in a buffer for the inevitable moment when the public finally decides to leave the car at home. It is far better to have a surplus that can be reinvested than a deficit that requires a taxpayer bailout of a controversial charging zone.

In Birmingham, the Clean Air Zone (CAZ) generated £25.6 million in net surplus in its first year, significantly outperforming initial cautious predictions. This variance was driven by a lower compliance rate than the 95 percent the council had modelled. When compliance is lower, penalty revenue surges, creating a temporary fiscal windfall. However, relying on non-compliance is a dangerous financial strategy for the long term. As drivers adapt and upgrade their vehicles, that revenue inevitably begins to erode, often at a rate of 10 to 15 percent per year. Plus, for a Clean Air Zone, the aim is partly to encourage drivers to drive compliant cars, which are assumed to be less polluting than those they scrapped.

This leads us to the fundamental paradox that sits at the heart of road user charging: the conflict between policy success and financial sustainability. In any other business, if what you do is so good that it changes the world, you expect to make more money. In road charging, if your policy is so good that it actually clears the roads, you go broke and can’t re-invest the money in sustainable transport. If the primary goal of a charge is to reduce congestion, then the ultimate sign of success is a city with empty streets. But empty streets do not pay for new buses, cycle tracks, and extended trams.

If the charge is too successful in changing behaviour, the revenue needed to fund the sustainable alternatives begins to evaporate. This leaves transport planners in a precarious position. If they set the charge too low, they fail to reduce traffic and the city remains choked. If they set it too high, they kill off the very revenue stream they need to pay for the buses that those former drivers are now supposed to be using.

London is currently navigating this with its recent announcement to increase the daily Congestion Charge from £15 to £18 from January 2026. This increase is specifically designed to combat the “revenue base erosion” caused by the rapid uptake of electric vehicles. The Cleaner Vehicle Discount, which previously exempted electric cars from the charge, is being phased out because TfL estimated that without this change, more than 2,000 additional vehicles would enter the zone daily by 2026. As we move towards a more electrified vehicle fleet, the traditional justification for charges on environmental grounds disappears, forcing a shift back toward congestion charges to partly keep the transport budget from going insolvent.

To understand why these schemes behave the way they do, we have to look at the nature of travel demand and the concept of price elasticity. In simple terms, price elasticity measures how much the demand for something drops when the price goes up. If the price of a luxury good doubles, you probably buy something else. That is high elasticity. But for many people, driving is not a luxury; it is a necessity.

Transport research in the United Kingdom has consistently shown that the price elasticity of demand for car travel is relatively low, especially in the short term. Most estimates suggest an elasticity coefficient of around -0.3. In English, if you increase the cost of driving by 10 percent, you generally see only a 3 percent drop in traffic. People are remarkably stubborn. They will grumble, they will cut back on other spending, and they will complain to the Council, but they will keep driving.

However, elasticity is not a fixed number. It varies based on the alternatives available. In Stockholm, where the public transport market share was already 77 percent before the charges were introduced, the elasticity was higher because people actually had a viable choice. In Milan, the introduction of Area C led to a 17 percent increase in underground usage and a 12 percent increase in surface public transport users. In a city with a patchy bus service, a road charge is less of an incentive to change behaviour and more of a simple tax on existing habits. This is why the investment in sustainable transport must often come before or alongside the charge. If you do not give people a way out, the charge remains an inelastic burden that raises money but does not actually fix the congestion.

As we look toward the next decade of transport planning, the financial model for road user charging is likely to change again. The rise of electric vehicles is already threatening the Treasury’s income from fuel duty, and local councils are watching their own charging revenues with a wary eye. Plus there is the ever-present issue of congestion posing significant economic externalities. In London, the 2024 congestion costs were estimated at £3.85 billion, or approximately £942 per driver, suggesting that despite the charges, the economic cost of gridlock remains higher than the cost of the fees themselves. Imagine what the cost would be without the charge.

The future likely lies in more sophisticated, distance-based charging that can be adjusted in real time based on congestion and air quality. But the lessons of the last twenty years remain. Success in this field requires a clear-headed understanding that a charge is a tool for change, not just a cash cow. It requires the humility to make boring, conservative forecasts that allow for the volatility of human behaviour. And above all, it requires an acknowledgement of the paradox at its core. If we truly want to create cities where people do not need to drive, we must be prepared for the day when the driving charges no longer pay the bills. The virtuous circle of the polluter paying for the bus is a brilliant way to start the engine of change, but eventually, we will need to find a more permanent way to keep the wheels of sustainable transport turning.