This blog, plus additional exclusive content, was published last Friday on my free Mobility Matters newsletter. You can sign up for the newsletter by clicking here.

Induced Demand is a sign of success, not failure

Prior to Christmas, I managed to start catching up on the some of the reading that I have been avoiding / have been too busy to throughout the rest of the year. One article of which was this by the always-excellent Tom Forth on the controversy surrounding Tim Leunig’s article on building lots of roads across the UK. In his concluding paragraph, Tom says…

But seeing the vicious reactions to Tim’s quite cautious piece on transport reminded me how difficult such a move would be, how strong the networks that reward cultural conformity and punish digression are, and just how poor much of our national debate on issues as mundane as transport is as a result.

Tom Forth

While I myself disagree with Tim’s solution to issues of connectivity between major cities, I agree with Tom, and in fact would go further. Much of our conformity or groupthink is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of key issues and human nature, based on evidence not tested properly for decades.

The worst offender here is the idea of induced demand.

For decades, “induced demand” has been the bogeyman of transport planning. It is often described as a persistent, almost mystical force that fills new lanes of traffic, packs out railway carriages, and crowds pavements the moment they are widened. It gained significant traction in 1994 with the publication of the legendary report of the UK Standing Advisory Committee on Trunk Road Assessment on Trunk roads and the Generation of Traffic. In this report, the conclusion was very clear.

Considering all these sources of available evidence, we conclude that induced demand can and does occur, probably quite extensively, though its size and significance is likely to vary widely in different circumstances.

UK Standing Committee on Trunk Road Assessment

A literature review by WSP and RAND in 2018 for the Department for Transport, and this analysis by Lisa Hopkinson and Phil Goodwin agree on this fundamental point, though disagree on the details.

Induced demand is often seen as a failure. It is a failure of forecasting, where additional unexpected trips cancel out the benefit of investment in infrastructure. It is a failure of transport policy which embeds car-centric planning. More recently, I have seen practitioners speak of “transport gluttony” where trips for certain people should actively be reduced.

I think differently to this. For me, induced demand is not a problem that must be solved. It is a sign of success. Furthermore, it is our job as transport planners to induce demand, and induced demand is an inevitable consequence of what we do. Induced demand is thousands of people visiting family, starting new jobs, and exploring the world in a way previously suppressed by poor infrastructure.

My hypothesis is this: induced demand is the surfacing of unrealised opportunities, and their gains likely outweigh their costs. Here, I will set out my reasoning for this.

At its core, induced demand comes about because new infrastructure creates a network effect that is often unknown until the concrete is dry or the tracks are laid. We tend to view transport projects in isolation—a bridge here, a bypass there—but the reality is that in the UK, we have a complex and highly developed web of transport networks. This means that the impacts of new schemes are often experienced well away from the immediate corridor on which they are delivered.

Let’s take a recently-completed scheme that is close to me: the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon Improvement Scheme. This massive scheme involved building a 12 mile bypass of the A14 around Huntingdon, junction improvements, widening the A1, and most iconically the demolition of the awful Huntingdon Flyover.

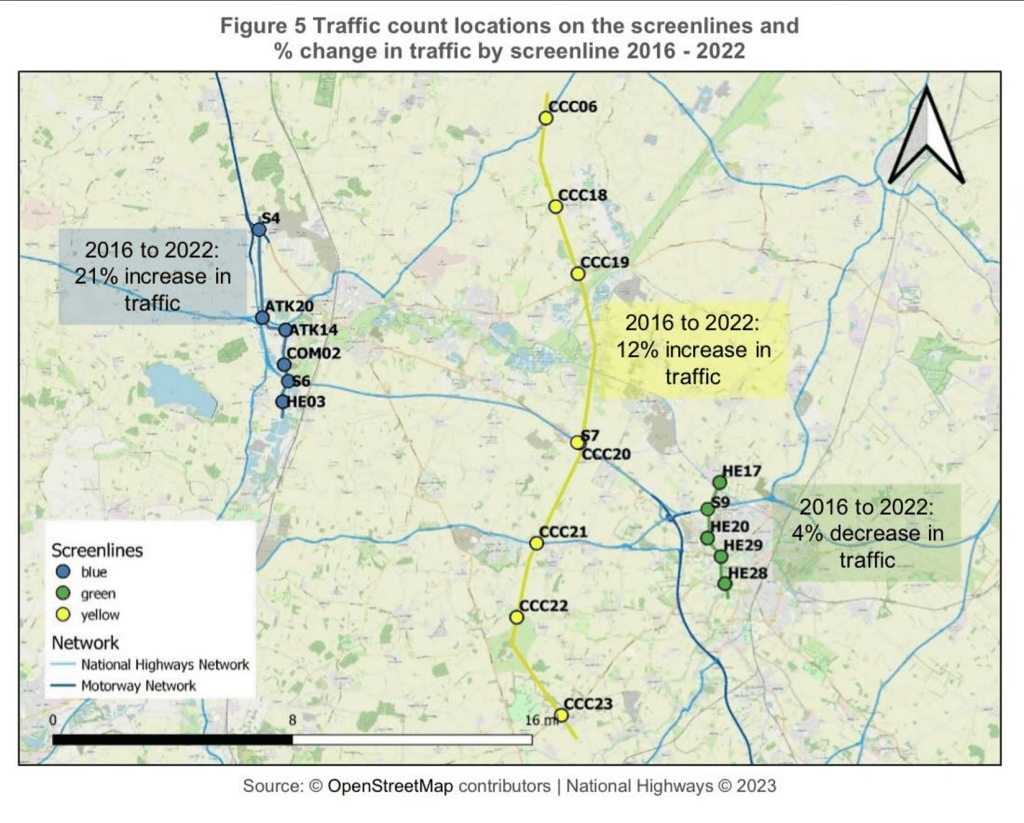

I won’t lie to you, this project was about increasing road capacity, and it did. The evaluation report of 2024 shows that every day, there are an extra 55,000 daily traffic movements along the corridor. Such additional trips were not just confined to the new bypass either. The A1 and A14 past Brampton has seen traffic levels increase by 21%, while there was a 12% increase in trips through places such as Willingham, Northstowe, Longstanton, and Dry Drayton.

But other locations saw decreases in trips. As far away as Impington and West Cambridge traffic levels have been observed to have fallen by 4%. But the most transformational impact has been on Huntingdon, where traffic levels on the old A14 fell by 76%. Where cars and HGVs travelling along one of the most important strategic roads in the country thundered past people’s houses, that same traffic passes miles to south. While other places see induced traffic, some places see induced peace and quiet.

Percentage changes in traffic by screenline 2016-2022 (Source: National Highways)

Furthermore, the relief of extra capacity gives the opportunity for other trips to take place. Yes, many of these are likely by car, as people take the opportunity to be where they want to be through driving when previously bumper to bumper traffic would have acted as a strong deterrent. But not accounted for are the smaller things. The kids being able to cycle with confidence now rat-running traffic is off the streets where they live. The old lady now feeling she can cross the road now that she doesn’t have a HGV waiting for her to get moving.

As for those extra 55,000 movements every day? That’s people going to business meetings, travelling to work, going to see family and friends. Trips not otherwise possible.

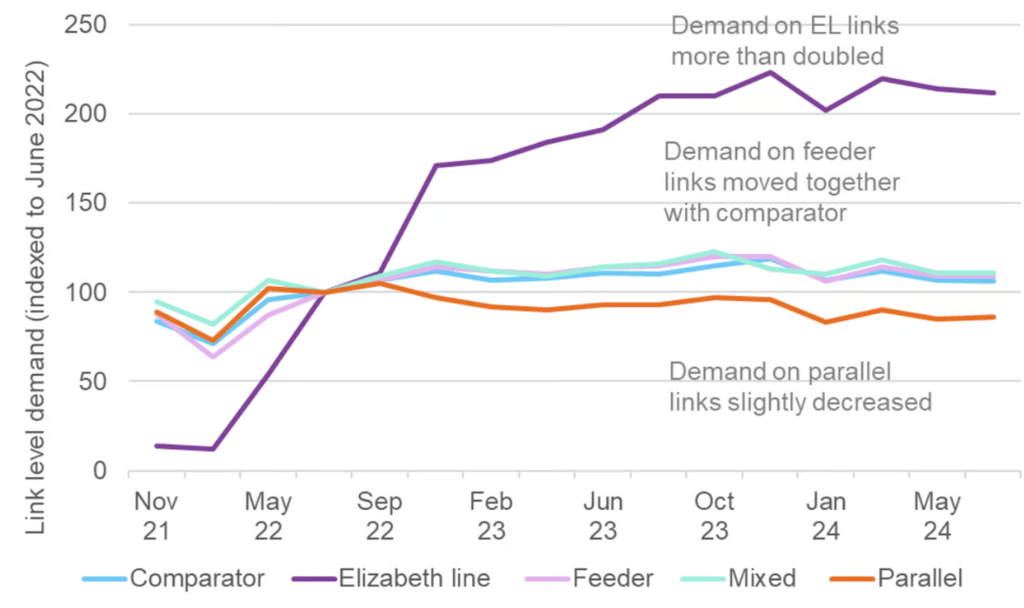

Lets take another example, and one that is the poster child of induced demand currently – the Elizabeth Line. By early 2025, passenger numbers on the line had stablised to around 500 million passengers a year – a figure consistently above every passenger demand forecast made for it. It has been a wildly successful railway, and a report by Arup for Transport for London gives some insight into why.

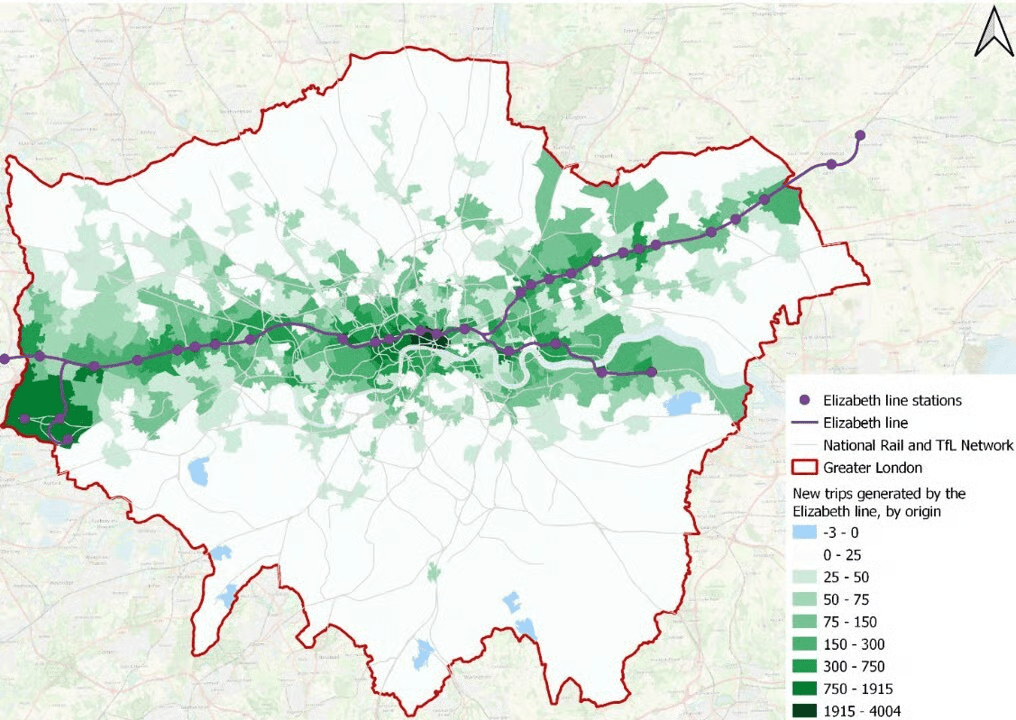

In this report, we see the wider network effects of improvements in infrastructure. Using a basic quasi-experimental analysis, the consultants estimate that at least 71,000 trips have happened on the Elizabeth Line that would not have had the line not be there. While the majority of these trips take place in the immediate vicinity of the line, there are significant additional public transport trips away from the line. Places such as Harrow, Enfield, Woodford, and Tottenham are notable concentrations of these additional trips.

Estimated new public transport trips in London, origin-based (Source: Arup & TfL)

The same report also gave an indication that such model estimates are not an outlier. Demand on parallel rail and London Underground links decreased slightly after opening, when accounting for demand on feeder links overall demand for rail and underground services (excluding the Elizabeth Line) was slightly above pre-opening levels. Furthermore, while 62% of passenger-kilometres on the Elizabeth Line in September 2023 were extracted from National Rail, London Underground, and the Docklands Light Railway, 38% came from modal shift and generated trips. The Elizabeth Line is positively an induced demand machine.

These are people who simply were not travelling before. The Elizabeth Line didn’t just move people; it created a “quantum leap” in accessibility. When you reduce a cross-city journey from 50 minutes of stressful changes to 20 minutes of air-conditioned comfort, the “disutility” of travel drops so low that new social and economic interactions are born.

You may be shocked for me to state that the Elizabeth Line is an example of induced demand. This is where I have a problem with the framing of induced demand. To me, induced demand is simply the manifestation of trips that would otherwise not be taken. Regardless of mode of transport. We try and induce demand for trips by public transport, walking, and cycling all the time, and we write policies and plans to do it. Yet we don’t call it that. We call it modal shift or reducing demand for car trips.

Doing so misses a fundamental fact about induced demand. Induced demand is an inevitable outcome of what we do. We might aim for modal shift from cars to trains, and we might achieve it. But we achieve induced demand as well.

There is a powerful economic argument for inducing demand: that of agglomeration. In economics, agglomeration refers to the benefits that arise when firms and people locate near one another. Transport infrastructure effectively brings people closer together without them having to move house.

When the Bee Network in Greater Manchester induced a 14% increase in bus patronage through 2024, it wasn’t just about more people on buses. It was about expanding the “effective labour market.” Though it has yet to achieve its goal for passenger numbers for 2025/26, by making travel cheaper and simpler through a £2 fare cap, the network “induced” trips from people who were previously “transport-poor.”

The mathematical impact of these extra trips is significant for the UK GDP:

- Labour Productivity: More induced trips mean a wider pool of workers can reach high-productivity jobs.

- Knowledge Spillovers: More face-to-face interactions lead to the sharing of ideas and innovations.

- Business Specialisation: Larger markets allow for more specialised businesses to survive and thrive.

Every “unexplained” trip on a bus or a train is a person contributing to this economic thickening. If we view these trips as a “problem” to be mitigated, we are effectively arguing against economic growth and social mobility.

If you think that the impact of the Bee Network experience is an outlier on buses, its useful to remember that when analysing the impact of the £2 fare cap, Systra and Frontier Economics estimated that a growth in bus passenger numbers of around 5% nationally could be attributed to the fare cap.

When you start looking at the evidence presented, you come to realise that transport planners seek to stimulate demand all the time – regardless of if we call it that. Within this, a philosophical point needs to be made. More trips equal more opportunities. We can, and should, argue about how people travel and the environmental impact of those choices. We should strive for those trips to be on the Elizabeth Line, or the Bee Network.

However, we must stop viewing the desire to travel as a negative. In the 2025 evaluations of London’s LTNs, researchers found that “walking stages” reached record highs. This demand was induced by the quality of the environment—people walking more because the “tax” of noise and danger had been removed. These trips often have no clear destination in an “Origin-Destination” matrix; they are “social strolls” or “exploratory walks” that improve mental and physical health.

We must accept that induced demand is an inevitable, and arguably desirable, outcome of any infrastructure improvement. Too much induced demand may be a bad thing, and can result in congestion and overcrowding as well as environmental impacts. But to take the view that induced demand only has downsides and no upsides is myopic, outdated, and – to me at least – wrong.

Whether it is the “Elizabeth Line Effect” or the revitalisation of a bypassed village, these projects show that humans have a deep, latent desire to connect. Almost all projects have unexpected demand impacts, some of which are induced by the sheer improvement of the experience. This is to be welcomed.

Instead of building infrastructure to “solve” a congestion problem, we should build it to invite an opportunity. Induced demand is simply the sound of a society waking up and using the things we have built for them. That should be celebrated.

As a starting point, I propose something simple. We update and expand the great work of SACTRA. We have a thorough review of the evidence across modes, and estimate both the benefits and costs of demand induced, and understand the human experience behind it. Maybe we can then get away from dogma and into evidence-led investment in delivering the infrastructure that is needed.