Sorry, no voiceover this week as my recording equipment broke! 😔

Good day my good friend.

I wanted to start off this message by doing a couple of belated thank you’s. The first thanks go to the amazing Transport Planning Society Regional Representatives who put on an amazing International Quiz recently. A fun evening was had by all, and lots of money was raised for charity. You are all legends.

Secondly, thank you to Sarah Barnes (of Along for the Ride) and Matt Clark’s for organising the Monthly Mobility Meet-up in London. Spending some time with like-minded people talking transport things on a sunny spring evening in London is a very good way to spend some time. If you fancy coming along to one, see Matt’s LinkedIn post for the details.

📕 I have co-authored a book on Mobility-as-a-Service, which is a comprehensive guide on this important new transport service. It is available from the Institution of Engineering and Technology and now Amazon.

💼 I am also available for freelance transport planning consultancy, through my own company Mobility Lab. You can check out what I do here.

⏩ Just Do It

The last few weeks have seen a flurry of announcements relating to big infrastructure projects in the UK. My LinkedIn has been full of commentary of the decision on the Lower Thames Crossing made just before this week’s Spring Statement. The Government is also minded to approve a second runway at Gatwick Airport. Also, the Chancellor of the Exchequer no less has thrown her support behind a third runway at Heathrow Airport.

It is well known that politicians like to announce big, shiny transport projects. Reviewing the Department for Transport’s press releases, since the start of the year ministers have proudly announced the preferred operator for East West Rail, improvements to the M3 near Winchester, 16000 new electric vehicle charging points for the Midlands, upgrading the A47 near Norwich, the A350 Chippenham Bypass, the A647 Dawsons Corner and Stanningley Bypass in Leeds,

the South East Aylesbury Link Road (SEALR), upgrading the A127/A130 Fairglen Interchange in Essex, a £295 million extension to West Midlands Metro, and Transport and Works Act Orders for the Cambridge South East Transport route and Old Oak Common. That’s a lot.

Its no shock that there is this level of activity. The National Infrastructure and Construction Pipeline (as of 2023) has transport as the second biggest government department in terms of major national infrastructure spend. Second only behind the energy sector. That’s a lot to announce.

The challenge, however, is getting things built. You will no doubt have heard of the stories, and the reasons why getting things built in the UK is such a challenge. That having a Third Runway at Heathrow has been spoken about since I started my career 20 years ago, and that the planning application for the Lower Thames Crossing now totals one MILLION pages are two facts that stick in my mind.

I don’t wish to discuss the relative merits of the Lower Thames Crossing or airport expansion here. What I am talking about is tackling the issue of delivery. Because, while we talk a big game on how to more effectively deliver transformational infrastructure, we don’t do it.

The UK, and the world more generally, is now in a situation where how it delivers infrastructure means delays. Which are as good as doing nothing, and right now doing nothing is not an option. The climate crisis is upon us. The British economy is dragging and incomes have not increased in any substantial manner for the better part of 15 years. We are more miserable than ever. There is also some evidence that poor transport links could mean voting for more populist parties.

The simple fact of the matter is that the UK needs to deliver significant infrastructure works, very quickly, and the current way by which major projects is delivered does not lend itself to quick delivery.

Others have made the case that simply unblocking planning legislation or removing judicial review will magically fix all of the infrastructure woes of the UK. There is a very interesting essay called UK Foundations, which I will write a reflection on soon, that articulates the challenges well and comes to the conclusion that deregulation is the answer. I have yet to see any compelling evidence of this. Regardless, government will still play a significant role in the delivery of major transport infrastructure projects in the UK.

Some of these ideas may work, but to me they miss something more fundamental. Namely that fundamental change is necessary to deliver such projects in line with best practice, and to do so quickly. Current reforms and ideas tinker at the edges and make small changes to try and make the existing system work better. A good example is the Infrastructure and Projects Authority. Announced as a way to speed up delivery, all it really does is provide project assurance, maintain the national infrastructure pipeline, and produce good practice guides and advice.

A couple of months ago I presented an idea in my response to the Integrated National Transport Strategy of establishing a Major Projects Accelerator. This is with the primary aim of taking major projects from idea to operation within 5 years through establishing a core capability in doing so. In the weeks since, my conviction that such an idea could significantly benefit delivery in the UK has only gotten stronger. Therefore, I wish to expand upon this idea here.

As the success of projects is based on the core capabilities of the staff who make it happen, it needs to be staffed with the best capability in major infrastructure delivery in the UK. Project Managers, Programme Directors, and Technical Leads from across transport infrastructure delivery who are committed to accelerating delivery and have direct experience of delivering such projects must be brought in. Ideally, technical leads from statutory stakeholders like Natural England and the Environment Agency should also be seconded into the Accelerator on multi-year contracts, and play a central role in project development.

The first task of any such accelerator will be to spend time considering the challenges associated with project delivery, and to develop a completely reimagined project template focussing on accelerated delivery. While best practice templates such as the Project Set Up Toolkit have been developed, they focus on flexibility of delivery approach, as opposed to delivering at pace while still meeting the requirements. This review needs to have as its core question “How can we deliver complex, major projects at pace?” as opposed to satisfying every possible requirement.

A natural constraint on such a template will be statutory requirements, such as biodiversity assessment or consultation. But rather than accepting established practice, the MPA should identify ways by which such legal requirements can be met, to a good standard, at pace. For instance, as opposed to undertaking Equalities Impact Assessments later in the design phase, engage with socially excluded groups and quantify potential impacts at an early stage, document them, and take action. There is significant potential to reduce time spent on such requirements, and deliver them to a higher standard, all while achieving what is required by law.

A most critical part of this work is to ensure that such a template is not constrained by the requirements of the Green Book. Whilst oversight of spending is necessary (more on this later), this is about trialling a new approach to major project delivery. Having constraints on the ability to deliver a new approach to accelerated project delivery by Treasury will limit the ability of the MPA to seek solutions outside of the narrow remit of what government appraisal mechanisms consider to be most cost-effective.

Once this task is completed, the projects to demonstrate this approach on need to be identified. While it may be convenient to focus on easy to deliver projects, a portfolio of projects of varying complexity across different sectors is essential to ensure that the new process is tested thoroughly and meaningfully. These should also be projects at a variety of degrees of development (from “apple in the eye” to near-strategic outline business case).

Once this project portfolio has been identified, a baselining exercise needs to be performed of traditional project performance, so that a comparator can be made when judging the success of the MPA. After all, the success (or otherwise) of this accelerator needs to be judged objectively, and comparing project performance against a baseline is essential for this. A series of indicators will need to be established, potentially measuring project delay against forecast, spend against forecast, and similar metrics for quality which are likely to vary by the sector.

A critique that can be made here is that due to the complex nature of major projects and local delivery circumstances, measuring against comparators in major projects will be difficult, and local factors are more likely to play a significant role in variances in projects. This is partly overcome by undertaking a comparator against a portfolio of projects, but also this critique can often be lazy, and implies that projects that run well are unaffected by local circumstances. I am often tempted to say that, when people say local issues have affected project delivery, that they need to provide evidence of how it has affected project delivery. But this is an aside for another time.

From this work, the practical elements of the delivery programme can then take shape, with all partners within the MPA feeding into development of this programme, critiquing it, acting as friendly challenge, but ultimately working towards a common goal of delivery within 5 years. At this stage, full sign off of the programme will be required through the appropriate approval mechanisms, duly expedited of course.

Complex major projects require a broad degree of political consensus. Working within the Westminster environment, the work of the MPA should ultimately be approved by the appropriate Cabinet Minister with a dedicated remit on Major Projects. This should sit outside Number 10 and the Treasury, so as to avoid risks of approvals being delayed through complex decision making processes within these organisations.

Political consensus could be maximised (though not eliminated entirely) through the establishment of a cross-party Oversight Board. Established in the early days of the MPA, this Board must provide political direction to the development of the accelerated programme, on the understanding that once the programme is approved future governments are, in effect, bound by its delivery. This Oversight Board could be chaired either by the Chancellor of the Exchequer or the Prime Minister.

You might argue that the House of Commons Transport Committee could play such a role and ensure that government is answerable to Parliament. However, this oversight would only be at times of its choosing as opposed to what ensures effective project delivery.

To ensure that progress can be assessed, progress reports against each project should be made monthly against all metrics as well as a useful project summary, providing full detail of any variances to timescales. No “watered down” language that gives little detail on progress should be provided in these update reports. This has an added benefit of providing contractors for delivery with an up-to-date picture on project progress, reducing their opportunity cost by understanding more accurately when project work is likely to be procured. It should be noted that, unless in truly exceptional circumstances, project work should only be contracted externally at delivery stage.

This, it is hoped, provides a basic framework on which to start an MPA which is sorely needed. The detail needs refinement, including precise skill sets required, staff or teams to second into the MPA, and of course the budget. Nor will the delivery of all of this ensure success. However, I consider that doing this means that major projects are delivered at accelerated timescales, without necessarily compromising on standards and priorities, or necessitating rounds of deregulation of the planning system (again, a matter for another time). Your thoughts, as always, are most welcome on this.

🚨Mobility Camp is back! 🚨

As I posted on LinkedIn on Wednesday, Mobility Camp is back this September. And as a member of the organising team, not only will I tell you how amazing its going to be over the coming months. This year is shaping up to be an amazing event, and I cannot wait to see you all there.

Starting with the vital things:

📆 Monday 29th September

🕛 9am to 5pm

📍 The amazing Techniquest in Cardiff

This year, the theme is Re-imagining the Rules. There is no shortage of rules in the transport sector, such as business cases for more infrastructure or best practice. Some rules are unwritten and are just ‘how things are done.’ Some are even interpreted in a certain way that has established behaviour that is detrimental to society, such as focussing on the economic benefits above over considerations. At this year’s Camp, you will explore what rules are holding us back from achieving the change that is needed, and importantly how they can changed or reinterpreted.

This year things have changed on the ticket front, and there are now three ticket types on offer.

🧒 For young professionals (aged 25 years old and under) we have a limited number of FREE tickets.

🏛️ Public and voluntary sector professionals get the usual discounted tickets at just £10 a ticket.

👩💼 Private sector professionals get an amazing value ticket for a fun and inspiring day at just £40 a ticket.

Tickets can be purchased online through Ticketpass. Part of their service fee they donate to charity, and you get to choose which one!

Plans for this year’s event are already shaping up, and its promises to be a good one. If you have no idea what a Mobility Camp is, there are write ups from previous events on the website.

👩🎓 From academia

The clever clogs at our universities have published the following excellent research. Where you are unable to access the research, email the author – they may give you a copy of the research paper for free.

Why do cars get a free ride? The social-ecological roots of motonormativity

TL:DR – People think others are less positive about measures to reduce car use than they are.

TL:DR – While many in 15 minute cities still use cars, they use them less.

On-demand ridesharing based on dynamic scheduling in urban air mobility

TL:DR – Someone uses a model to optimise scheduling of urban air services.

TL:DR – Shockingly, women have a different experience of safety in urban environments than men.

🖼️ Graphic Design

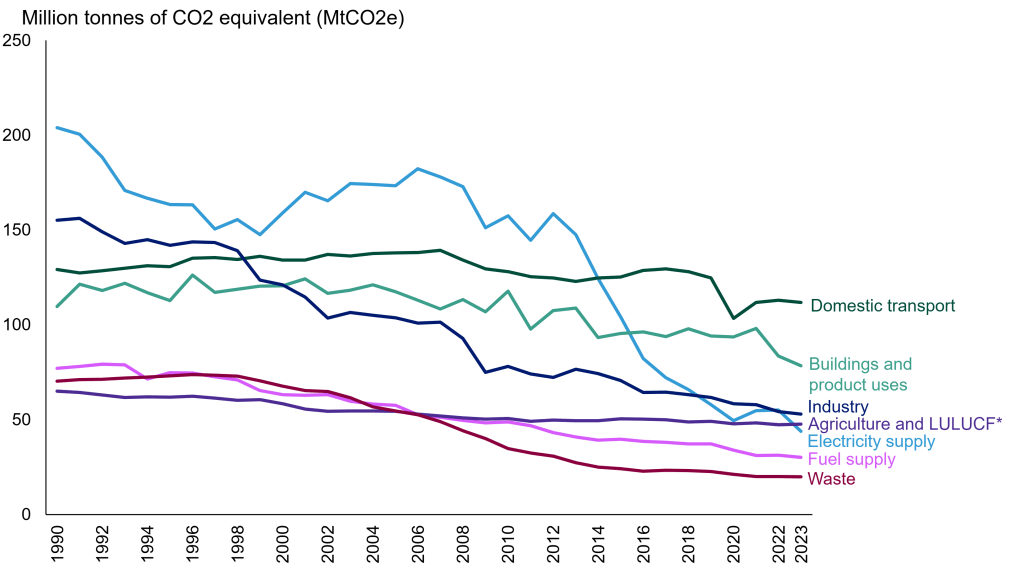

Domestic greenhouse gas emissions by sector, 1990 to 2023 (Source: DESNZ final UK greenhouse gas emissions 2023)

Some good news. While we are not decarbonising the transport network fast enough, carbon emissions are still 10% below 2019 levels. At least in the UK.

📺 On the (You)Tube

How do you build a major transport interchange underneath major historical landmarks? Well, we have been doing it for centuries, but this is the example of Westminster when the Jubilee Line extension came along.

📚 Random things

These links are meant to make you think about the things that affect our world in transport, and not just think about transport itself. I hope that you enjoy them.

- Microplastics: What’s trapping the emerging threat in our streams? (Phys.org)

- Exclusive: Anthropic warns fully AI employees are a year away (Axios)

- Climate Change: Where are We and Where are We Going, in Five Recent Books? (Naked Capitalism)

- No more heroes: or, seeking strong gods (Chris Smaje)

- LinkedIn’s unlikely role in the AI race (The Economist)

📰 The bottom of the news

Its probably one of the most iconic cars ever made, despite being widely considered to be an awful one. But there are fewer of them. The DVLA confirmed that there are just over 300 DeLorean’s left in the UK.