By downloading this file, you can listen to this newsletter on the go, or as an alternative to your screen reader. And it’s in my voice! 😊

Good day my good friend.

This week has been a flurry of transport-related announcements, and a week of me pounding the rails for work. So I’m just going to get straight into it.

📕 I have co-authored a book on Mobility-as-a-Service, which is a comprehensive guide on this important new transport service. It is available from the Institution of Engineering and Technology and now Amazon.

💼 I am also available for freelance transport planning consultancy, through my own company Mobility Lab. You can check out what I do here.

🛫 Airport Expansion Economics

This week has seen the Chancellor of the Exchequer state that it is the government’s position that the third runway at Heathrow Airport must proceed. Before auditioning to be a stand up comedian by saying it should be completed and operational within 10 years.

There are a lot of reasons for and against the expansion of airports. But as the government is positioning this as that of economic necessity, I thought it useful to give a short primer on the economic impacts of airport expansion.

To me, understanding the economic impacts of any transport scheme boils down to two things. First is the actual estimated benefit, and the second is the benefit most acutely felt by people – namely jobs, incomes, and costs.

So, what is the economic benefit of airport expansion?

In making the economic case for airport expansion anywhere, the difficulty lies in what that economic benefit constitutes. We have a means of assessing and quantifying economic benefits of transport schemes through TAG. Despite its flaws (and there are many), there is at least consistency in methodology to enable some degree of comparison between schemes.

The Airports Commission, which reported in 2015, used this as a basis on which to articulate the case for airport expansion in the UK. There are plenty of issues with this analysis, and the Department for Transport’s own review of the Commission’s final report is great if you want to know more about this, but for now I am using this analysis to articulate a wider point, as opposed to commenting on its quality.

In airport expansion at places such as Heathrow and Gatwick, the majority of the economic benefit is in ‘consumer surplus.’ In economics, this is mostly the difference between the price willing to be paid by a consumer and the price actually paid. For example, lets say you want to fly from London to New York, and you are willing to pay £1000 to do it. But you find a ticket that does everything you need for £500. The £500 difference is your consumer surplus.

In the situation at Heathrow, we have an airport that is at capacity. A congested airport has costs, some of which are actual (e.g. more fuel burned while circling waiting for a landing slot), and others reflect demand. In our case, because people want to fly into Heathrow compared to, for example, Luton Airport, they are willing to pay a premium for it, so the airlines charge more. This reduces the gap between the price paid and the price willing to be paid.

This reduction in consumer surplus is considered a bad thing economically. A greater consumer surplus means that, in theory at least, consumers have more money to spend in other areas of the economy. By expanding capacity at a congested airport, this frees up landing slots for competing airlines and new routes, which reduces fares for consumers, and thus generates a greater consumer surplus.

The other side to this is producer surplus. This can be best understood as the producer of the service (in this case, the airlines who fly the routes) pocketing the benefits themselves. In this example, airlines may benefit from reduced delays on the ground and circling the airport, reducing fuel burnt and increasing aircraft and crew utilisation. Rather than passing that saving onto customers, they keep it themselves. This weakens the economic case for expansion as the benefits are realised to companies, but not the wider economy.

The reality is that any kind of airport expansion features a mixture of both consumer and producer surplus. The economic case therefore hinges on this balance. If the airlines pocket the savings, the case for expansion is weak. If consumers get a better deal, it strengthens the case.

What’s more, different consumers have different levels of willingness to pay. As a general rule, business passengers are willing to pay a higher price than leisure travellers, and so the balance of customers affects the economic benefits that are realised. Taking our earlier example of a flight between Heathrow and New York, a leisure traveller may be willing to pay £1000, but a business person who has had to dash to the airport at the last minute may be willing to pay £2000 to be on the same flight. If your airport serves more business people, the case for expansion is better.

This is all something that is commonly misunderstood when politicians speak of economic benefits. There is an economic value in such things that, assuming there is a perfect market in operation for air services, would be realised by the wider economy in an indirect way. This is where most of the economic benefit of airport expansion can be found.

But this is not something that is necessarily felt by people. People feel economic effects through having jobs, boosting their income, or some things costing a little less than they did before. This is the real world of economics, and it is one where the case for airport expansion is explained, but is difficult to feel.

Take jobs, for instance. In theory, more passengers through an airport and more flights serviced means a greater demand for ground crews, security staff, and barista’s serving coffee in departures. Heathrow Airport itself is a huge employer. 76,000 people work at the airport. That’s the same number of people who live in Chesterfield.

There is also some evidence that shows airport expansion can have knock on benefits to employment outside of the airport. Heathrow itself says that it supports the jobs of 112,000 people, and I can believe it. When Amsterdam Schiphol Airport was expanded, every additional job at the airport created an additional regional job. This is contingent on other factors, such as nearby universities and the location of the nearby city.

When it comes to incomes and costs, the economic literature contains no firm conclusions in terms of impacts that people can feel. But there is some useful insights. For example, experience from the expansion of Chicago O’Hare Airport has shown that the effects of expansion on house prices is to actually increase them. Mainly due to the effects of accessibility, and aircraft being much quieter than anticipated. This is not to say that there is no economic disbenefit, as other research in Memphis shows that for every decibel noise increases there was an average external cost of $4,795 experienced.

If you are somewhat confused by all of this, you have every right to be. Transport schemes rarely deliver economic improvements by themselves directly, particularly in terms of the number of jobs and improvements in income. They enable other areas of the economy to realise economic benefits through generating consumer benefits. Benefits that are subject to a variety of influences outside the control of transport.

So this poses the question: is the expansion of Heathrow worth it economically? My instinct is that it will probably have a beneficial economic impact. But that doesn’t make it the best option for expansion, nor does it mean that expansion itself is a good idea.

If I am putting my cards on the table, I am against the expansion of airports above their current capacity. Not only is it incompatible with our climate goals, but assuming expansion is desirable, there is plenty of runway capacity at existing airports across the South East to grow flights. Simply expanding Heathrow because everyone wants to fly to Heathrow doesn’t fly with me (pun intended). Not only that, but the cap on landing fees at Heathrow needs to go.

But I hope that, from this newsletter, you at least have the basic understanding to interpret the economic case of any airport expansion, so you can make up your own mind. This is a big issue affecting transport in the UK. The least you can do is come to an informed view on it.

👩🎓 From academia

The clever clogs at our universities have published the following excellent research. Where you are unable to access the research, email the author – they may give you a copy of the research paper for free.

Future of Passenger Mobility in the U.S.A.: Scenarios for 2030

TL:DR – This research sets out work undertaken to identify three plausible scenarios for the future of passenger transport in the USA out to 2030. I wonder if any of them include a President signing an Executive Order blaming “DEI hires” for a major air crash?

Are Toll Facility Travelers Aware of Their Toll?

TL:DR – Just over 80% of toll facility users do not know how much the toll was. Despite having paid it. It sounds mad, but its a good exploration of the concept of willingness to pay.

Decarbonising the land transport sector: Pathways towards enhanced global governance

TL:DR – There are significant gaps in global governance of the transition to Net Zero emissions. This article proposes a series of changes to fill these governance gaps.

Parking, travel behavior, and working from home

TL:DR – People who have free parking either at home or at the office are much less likely to work from home.

😃 Positive News

Despite there being a lot of opposition to them, some councils have continued to back cycle lanes in their patch. The Binley Cycleway has again been backed by the Council, and a plan for 28 cycle lanes has been backed in the Wirral.

On the buses, some areas in Oxfordshire are seeing increases in demand so much that single decker buses are being replaced by double-decker buses. While Stamford in Lincolnshire has a new bus service linking to the station.

On the railways, there will soon be a new station in Wales. As Cardiff Parkway in the east of the city was recently approved. Oh, and the government has supported the East West Rail project for the billionth time. How about we get it built?

🖼 Graphic Design

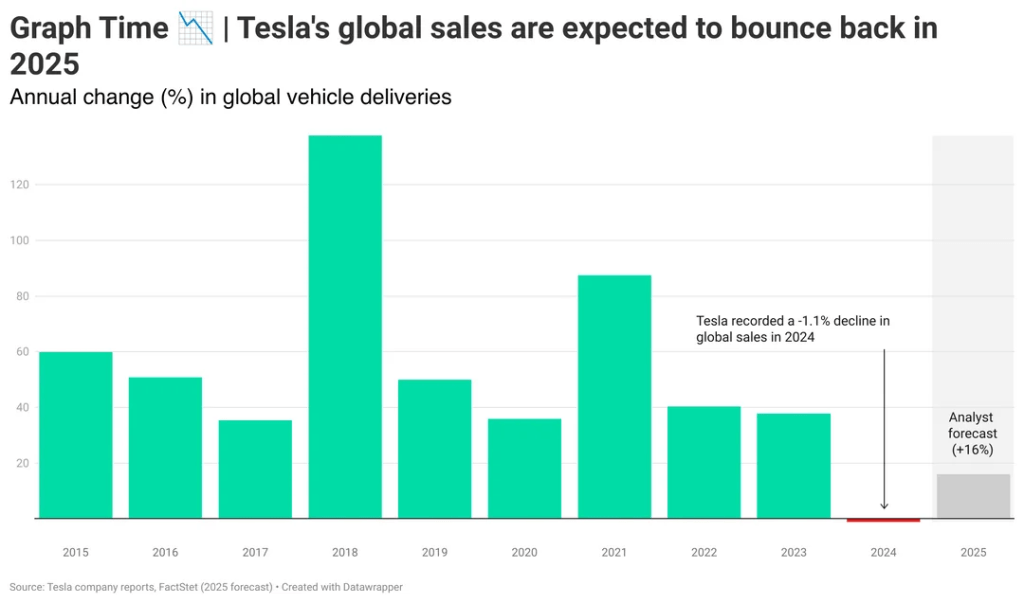

Changes in sales of Tesla vehicles globally every year since 2015 (Source: r/databeautiful)

Tesla, along with other electric vehicle manufacturers and models, has had a good decade of growth. With growth in vehicle sales exceeding 35% every year since 2015. But 2024 was different, as sales fell by 1.1%. I really hope that its because of their CEO and his ‘political views,’ but I suspect that the reasons are more complicated than that.

📺 On the (You)Tube

I always enjoy it when one of my favourite non-transport YouTube channels comes over all urbanist. This week, it is the turn of the excellent football channel HITC Sevens, which explored why American stadiums are so dystopian. In short, they are surrounded by car parking and located in the suburbs, while European stadiums are typically well served by public transport.

📚 Random things

These links are meant to make you think about the things that affect our world in transport, and not just think about transport itself. I hope that you enjoy them.

- Fake papers are contaminating the world’s scientific literature, fuelling a corrupt industry and slowing legitimate lifesaving medical research (The Conversation)

- How Climate Change and Widespread Unaffordable Home Insurance Will Wreck Property Values (Naked Capitalism)

- How pandemic helped the far right rise to power and what can be done about it (European Pravda)

- We Need To Get Off The Internet (Defector)

- Mother Load (Orion Magazine)

🙏 A favour to ask

Over the last few months I have been helping the Scottish Rural and Islands Transport Community with a report on Rural Island Mobility Plans. Their Stage 1 Report has now been released, and they would love comments on it. So please read it, and send any comments to sritc@ruralmobility.scot.