Good day my good friend.

Its been a while, hasn’t it? I hope that you are well and that you have had a lovely break away from the stresses of life. I know that I have, and it was joyous.

As I promised, things have changed around here. So let me give you the grand tour. At the top of this newsletter you may have noticed an audio file. This is for those of you who struggle to read what i have written, either because you need a screen reader to read text, or because you don’t have time to read. It’s my first attempt at this, so let me know if you like it!

The positive news section is back, focussing on good news stories and people doing good things to change the world. Speaking of which, I read Hannah Ritchie’s book Not The End Of The World over the Christmas break. You have to read it, especially if you are depressed about the state of the world.

As for content, I am going to provide some more structure to what i write about, as opposed to writing about what I feel like. This is being aided by two things. Firstly, I am going to write a book myself, with the current subject about how transport can fix a Broken Britain. Secondly, I have some research projects planned that I will be reporting on.

Okay, that was a rather lengthy introduction. So let’s get back into it.

📕 I have co-authored a book on Mobility-as-a-Service, which is a comprehensive guide on this important new transport service. It is available from the Institution of Engineering and Technology and now Amazon.

💼 I am also available for freelance transport planning consultancy, through my own company Mobility Lab. You can check out what I do here.

🖐 Defending the South East

Over the years, there has been much written and said about regional inequality within the UK. With the common narrative being about how ‘the North’ has lost out to transport investment compared to London and the South East.

To be fair, much of this is correct. As the excellent Tom Forth has written over many years, Britain’s regional cities perform poorly in transport terms relative to their European neighbours. For instance, Sheffield is the largest city in Europe that has train services that are not electrified. While Coventry has a population of 316,000 with no tram services. For comparison, Mannheim in Germany – population 311,000 – has 10 tram lines.

The one exception to all of this, however, is London. However much we decry it, it has one of the best public transport systems in Europe. The numbers speak volumes in themselves. Of the top 20 busiest railway stations in the UK, just 5 are outside of London. Highbury and Islington station – which is a relatively minor station on the Northern City Line, Mildmay Line, Windrush Line, and Victoria Line – handles more rail passengers than Edinburgh Waverley. London Underground handles more passengers than the entirety of the National Rail network. In 2023/24, 51% of all bus trips in England were in London. I think you get the message now.

This gives rise to the narrative that the South East or the South is favoured in transport decision making. For example, when commenting on cuts to HS2, Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham said:

That would be the same old story – a “money no object” approach to transport investment in the South as we have seen with the bail-outs for Crossrail – and a penny-pinching one in the North.

I hope to come back to this matter of regional inequality in transport in the UK later in the year, as its worthy of a deep dive on its own. My instinct is that the likes of the Northern Mayors are right when it comes to major transport investment outside of London, but I cannot say for certain.

But lets work on the assumption that the South East has been favoured a lot by British transport policy makers over the years. What has this meant for the South East? Over the last 18 months, I have been working at Transport for the South East, the sub-national transport body for the South East, to understand the nature of the issues faced in the region. This work has revealed to me both the issues of (comparative) success and its unequal distribution.

I should state here that what I mean by the South East is the Transport for the South East area. This covers Berkshire (including Reading), Hampshire, Portsmouth, Southampton, the Isle of Wight, West and East Sussex, Brighton and Hove, Surrey, Kent, and Medway. When the South East is often spoken of, its in relation to the International Territorial Level (otherwise known as NUTS), which also includes Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. Some also include London, and others even add in Hertfordshire and Essex. When referring to the South East I will be referring to the Transport for the South East region, unless specified otherwise.

In terms of the concentration of economic activity among the UK regions, the data is very clear. In 2022, the Gross Value Added per annum by region had the South East NUTS region at £307m, only beaten by London (about £470m). Local authority-level estimates of GVA are hard to find, but there is variability within the region.

For instance, looking at variations in earnings, there is a clear variation across the region. The areas with the highest concentration of high average incomes (greater than £60k per annum) is found around Berkshire and North Surrey. With areas like Bracknell, Maidenhead, Woking, Guildford and Epsom being particularly high concentrations.

Average household earnings in the South East Region (2022) (Source: TfSE Need for Intervention Report) – Sorry for the blurred image, it is the best I could source

Data from the Centre for Cities also reveals that even within the South East, economic growth is incredibly concentrated, although being more widespread than it is across many other regions of the UK. Among the top 10 cities across the UK in terms of GVA per hour in 2021, 5 are in the South East:

- Slough (£62.90 GVA per hour)

- Aldershot (£59)

- Worthing (£51.50)

- Reading (£48.60)

- Crawley (£40.70)

Despite this, there is evidence that poor connectivity is holding back the economic potential of many South East cities. Notably Portsmouth (£36.23 GVA per hour) and Southampton (£35.64), which are connected by the congested M27 and poor rail links that take up to an hour to travel 15 miles.

To further prove that not all success is equal, using Transport for the North’s data on Transport-related Social Exclusion we can see that transport plays a role in the significant exclusion issues faced across the South East. Namely that far from being the hive of connectivity often associated with the South East, there are areas with significant issues.

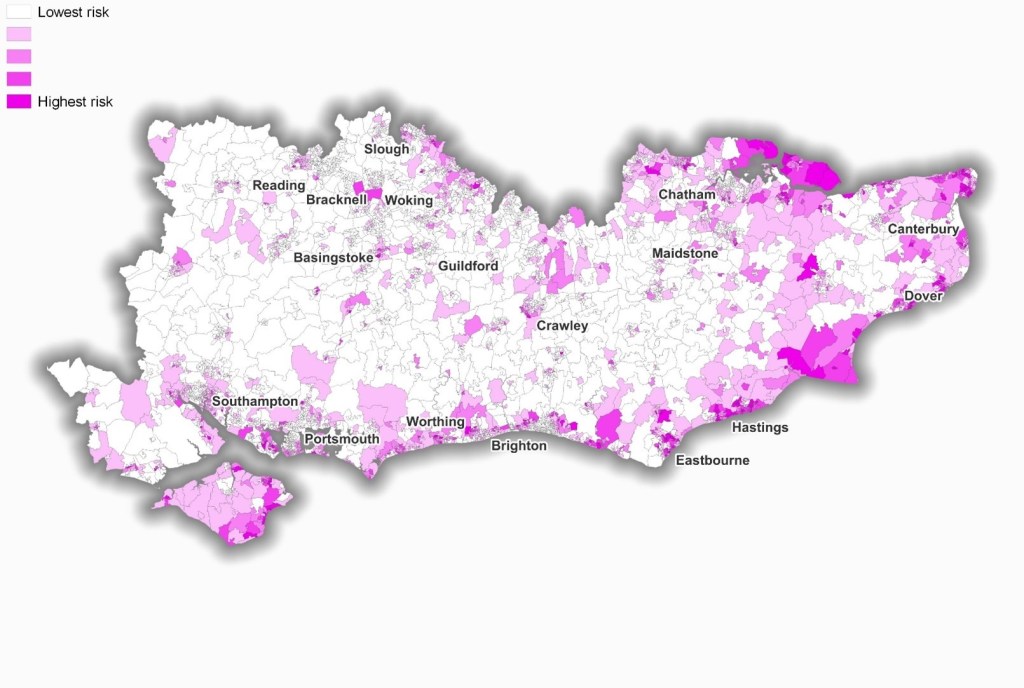

Areas at risk of Transport-related Social Exclusion across the South East (Source: TfSE Engagement with Socially Excluded Groups, Transport for the North)

Areas at the highest risk are particularly concentrated around the coast, notably Kent and West and East Sussex. In fact, the district with the highest percentage of the population at risk of Transport-related Social Exclusion in the whole country is in the South East: its Hastings at 83.9% of the population. Though it should be stressed that, because deprivation is quite low across much of the South East, the overall regional figure for Transport-related Social Exclusion is low – at just 16.4% of the population at risk.

When it comes to transport connectivity, a slightly simpler message emerges. Namely that if you are on a radial route into and out of London, connectivity is excellent. Otherwise forget it. Take average rail journey speeds as an example. On the radial routes into London, speeds are often in excess of 60mph on average. But going across the region, such as on the North Downs Line and on the Coastway route between Southampton and Brighton, it struggles to get to 40mph. It also leads to situations where travelling via London can often be quicker than getting a direct train between two stations.

Average rail journey speeds between major urban areas around the South East (Source: TfSE Need for Intervention Report)

The layout of the major road network is similar. Radial routes are dominated by motorways (M4, M3, M23, M20, and M2) and strategic roads upgraded to dual carriageway standard (such as the A3 and A23). Meanwhile, strategic non-radial highways consist of single carriageway local roads, the A27, and the M25, The M27 between Portsmouth and Southampton is the exception here, and experiences heavy congestion.

A final relevant factor that regional imbalances investment creates is one of resilience. Namely, because specific bits of infrastructure become so overworked and relied upon, when they break they have national implications. This is especially the case in the South East.

Consider this. Either within it or on its doorstep, the South East has the following:

- The two busiest airports in Britain. One of which is the busiest airport in Europe (Heathrow – 79 million passengers in 2023), and the other is the busiest single runway airport in the world (Gatwick – 41 million passengers in 2023);

- The second busiest passenger ferry port in Europe (Dover with 8.9 million passengers in 2022);

- The busiest motorway in the UK, and possibly the busiest in Europe (the M25);

- The busiest river crossing in the UK (Dartford Crossing, with over 130,000 vehicles using it daily);

- The third busiest port in the UK for container traffic (Southampton) with the second busiest (London) on its doorstep;

- The only section of High Speed Rail Line in the entire country, namely High Speed 1.

That is a whole lot of busy, and consequently within the South East it changes the strategic argument for investment in infrastructure away from economic growth to that of resilience. Namely, because these congested networks are so critical as economic activity is concentrated through these congested points and corridors.

Some of this can be put down to an accident of geography. Dover just happens to be the closest point in the UK to mainland Europe, and so it makes sense to have a ferry crossing here. Even HS1, designed to link London to the Channel Tunnel, could not be put anywhere else apart from through Kent.

But others are very much a result of choice. Heathrow was chosen to support a growing London, and upgrades to railways have rested on supporting London commuters (with a cynic also saying that these upgrades make better the commutes of those working in Whitehall). Because investment may not have been focussed in other regions of the UK in the past, this has impacted on the South East and not always in a positive way.

The net result of this is several things. The South East has, generally, benefited from regional disparities in the UK. But these benefits are by no means universal, and they raise resilience challenges. If you are on a radial route to and from London, the good times roll. Otherwise, its not so easy. Plus if any of the major pinch-points fall over, it has national implications.

Transport’s story when it comes to the regions of the UK should, therefore, not just be about growth or levelling up left-behind regions. But it should also be about reducing pressure within successful regions and tackling intra-regional disparities as well. London and the South East should not have to carry the weight of economic prosperity of the UK on its shoulders, as it has very real transport issues.

👩🎓 From academia

The clever clogs at our universities have published the following excellent research. Where you are unable to access the research, email the author – they may give you a copy of the research paper for free.

TL:DR – If older drivers are given driver education, they are more likely to restrict their driving to local areas, and the safety impacts are not noticeable.

TL:DR – There may be evidence that transit-oriented developments have helped passenger numbers to recover at the stations they are close to, set against a general backdrop of recovering passenger numbers across the system.

Changes in mode use after residential relocation: Attitudes and the built environment

TL:DR – If people move to urban areas, they are more likely to walk and cycle more, and are likely to use cars and public transport less.

Sustainability in transit: Assessing the economic case for electric bus adoption in the UK

TL:DR – There is not much cost difference between electric and diesel bus fleets, but it depends on the size of the operator and the nature of network operated. Smaller operators need subsidy.

😃 Positive News

In Southampton, work has started on the Portswood pedestrianisation scheme. This will be trialled for 6 months before a decision is made on whether to make it permanent. I hope that it is.

Paris has been doing a lot of good things to reduce car use in recent years. An article on ZME Science has gone into detail on this and how it was done. Here’s a clue: political support helped a lot.

Glasgow is also trying to do great things. One of them is the Avenues Plus Project where John Knox Street and Duke Street will be transformed to include bike lanes and rain gardens. Bikes and trees are good, don’t you know?

Greater Manchester has taken back control of more buses in Manchester. Though in a somewhat sad news this has meant the end of the Magic Bus, which I fondly remember riding along Oxford Road whenever I visited some of my in laws in South Manchester.

Meanwhile across the Pennines, not only has the consultation on bus franchising in West Yorkshire just closed, but Leeds City Council are consulting on improvements to the A64 that will speed up bus journeys. So things may be on the move there – literally.

🖼 Graphic Design

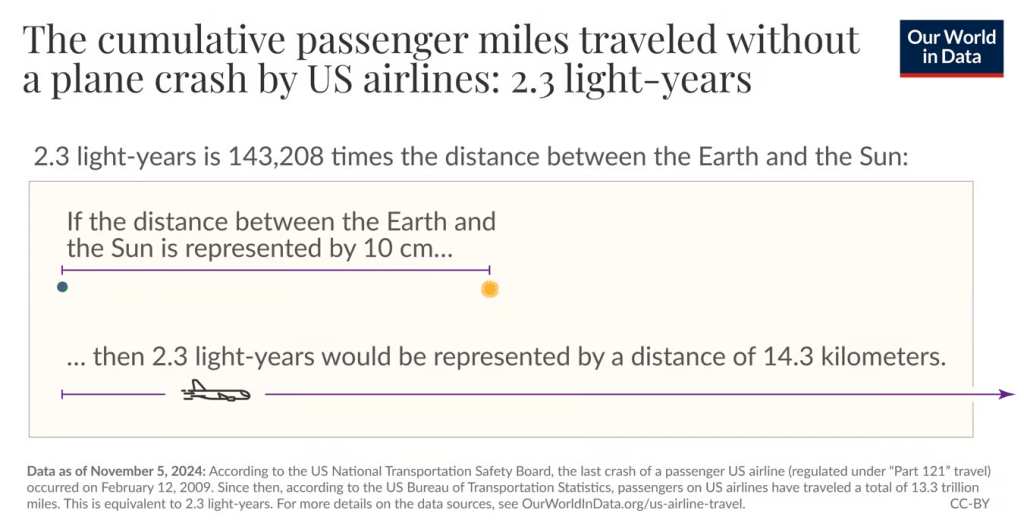

Comparing light years flown by airlines in the US to the sun (Source: Our World In Data)

This will be a challenge for the audio recording won’t it? But when the always-excellent Our World in Data reports that US airlines have flown for more than 2 light years since the last plane crash. Put simply, the last fatal crash of a passenger jet in the USA was in 2009, and since then US airlines have flown 13.3 trillion miles. A light year is 5.9 trillion miles, and so you do the math.

To put that in context, that’s half way to Proxima Centauri, the nearest star outside of the Solar System which is 4.25 light years away. As for Britain, well, I don’t have the figures for the distance flown, but I know that the last crash of a passenger jet in the UK where passengers were killed was the Kegworth Air Disaster on 8th January 1989.

📺 On the (You) Tube

Long time readers will know I am a huge fan of Geoff Marshall. And about a month ago he published an excellent video of him and various other railway YouTubers travelling to Northampton station. Why? Its for the All Aboard to Northampton project, where a worker at Northampton station is collecting examples of tickets from every station in the UK to Northampton.

📚 Random things

These links are meant to make you think about the things that affect our world in transport, and not just think about transport itself. I hope that you enjoy them.

- Are tech firms giving up on policing their platforms? (New Scientist)

- Who Owns the Air? (Econlife)

- Why are governments so bad at problem solving? (Undercover Economist)

- They Missed Their Cruise Ship. That Was Only The Beginning (Curbed)

- DOGE: Nations Aren’t Corporations and ‘Efficiency’ Means Austerity (The Journal of Belligerent Pontification)

📰 The Bottom of the News

You probably saw this before Christmas, but this story of the US city of Bend in Oregon about people sticking googly eyes on statues made me laugh. It also goes to show that if you are a council, never, EVER tell people not to do something silly.