Good day my good friend.

It is done. The book on Mobility as a Service that, along with fellow author and all-round-good-egg Beate Kubitz, has taken the better part of 4 years to write is off to the publisher today. If you ever want a project that requires sheer will to get done, I heartily recommend writing a book.

If the recent announcement by the Prime Minister still has you hot under the collar, we are talking ‘changing the narrative’ on sustainable transport at Mobility Camp on 26th September 2023 in Birmingham. It would be great to see you there. Get your tickets now.

If you like this newsletter, please share it with someone else who you think will love it. I will love you forever if you do. ☺️

James

💦 Traffic isn’t like water

It’s been at least a week where I haven’t spoken about Low Traffic Neighbourhood’s. But an article in The Guardian – and a poorly implied headline I might add – has forced me to consider an aspect of LTNs often debated but with very little evidence much of the time. That of rat-running traffic, or for those of you not native to the UK, traffic diverted into residential areas from busier roads on the periphery.

Does rat-running happen? That’s a silly question. Of course it does. Such roads carry a significant proportion of all traffic and one that has been increasing in many areas due to the prevalence of satellite navigation systems such as Waze. The challenge here is the relationship between such traffic and solutions that discourage it. To which there is evidence that it does.

Whether it is studies about the effects of LTNs put in during COVID-19, or looking at traffic within the LTN area, the effect is the same – they reduce traffic within the affected area. But this is where traffic starts to become interesting. Often it is considered that traffic runs along streets like water through pipes. When in fact traffic does not act like water at all.

A famous study, often quoted and misunderstood by people advocating against LTNs, by Sally Cairns, Stephen Atkins, and Phil Goodwin, revealed that traffic does not act in this way because of a simple thing: humans. The water analogy assumes that, like water, traffic is an unstoppable force of nature that consistently happens. But the humans behind the wheel can do something that water cannot – choose not to travel. That results in traffic evaporation (as well as switching to other modes) which is where the benefits from such schemes actually occur.

In many ways, that is an incredibly powerful thing. LTNs are often seen as something that restricts choice. But often they show people what choices they have in how they get around, especially locally, by simply making the default choice slightly harder. Seeing such choices is not freedom to drive, but showing a freedom we don’t often see – the freedom to choose not to.

What you can do: If you are promoting a low traffic neighbourhood, have a conversation with a specialist in PR about different concepts of freedom. They will likely give you great advice on how to promote your scheme as a different type of freedom compared to the freedom to drive. They are likely to also recommend getting a few case studies of people who have made that change – stories are great for selling the message!

💡 Occasional Inspiration

This weekend, along with my wife I celebrated my 19th wedding anniversary with a trip to London. As well as shopping, eating, and other such treats, I simply had to take in a transformative transport infrastructure scheme – Strand Aldwych. Seeing a former traffic sewer changing to a fantastic public space is incredible, and the space is radically different compared to what it was.

Naturally, I had to take some pictures. Including a selfie of a peice of London Underground heritage that I took while my wife wasn’t looking.

What you can do: The Strand Aldwych website has a full timeline detailing every step the team went through from start to finish. So if you want to recreate the scheme completely, they have a complete walkthrough for you.

I would highly recommend a specific approach they took – including an artist as part of the design team. They can engage with people in ways us transport professionals cannot.

🎓 From academia

The clever clogs at our universities have published the following excellent research. Where you are unable to access the research, email the author – they may give you a copy of the research paper for free.

Cutting social costs by decarbonizing passenger transport

TL:DR – Decarbonising costs a lot now, but it will cost more in economic and social terms if nothing is done.

TL:DR – Older people walk in funny ways. Spacially at least.

TL:DR – Yes.

TL:DR – Caring is radical action.

📘 Reading for the train

At the weekend I picked up and ploughed through the excellent Longitude by Dava Sobel. Its about one of the greatest scientific achievements of the 18th Century (estimating longitude) and the life of one of transport’s unknown genius’ – the clockmaker John Harrison. And its a highly enjoyable read.

If you don’t have the time to read it, I recommend you make it. Failing that, the brilliant Map Men made a very funny video about Harrison.

✊ Awesome people doing awesome things

📼 On the (You)Tube

Geoff Marshall rides the extension of the Edinburgh Tram. Trams are good. We should build more trams.

What you can do: If you are UK-based, I highly recommend reading the Midlands Metro Alliance Project pages, which are essentially a guide on how to build a tram system in a country that seems dead set against it. Read how they are delivering each aspect of tram extensions in the West Midlands from inception to construction.

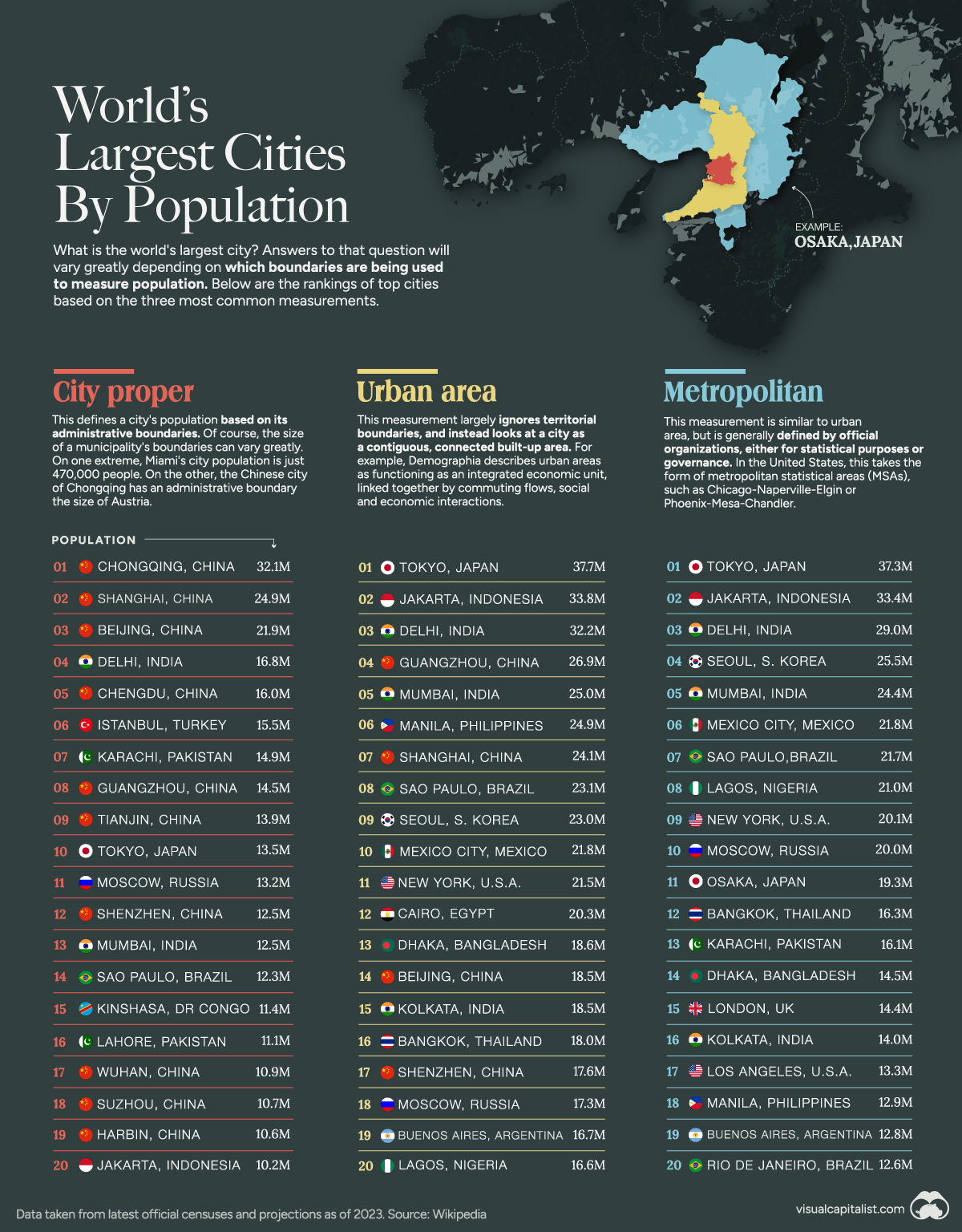

🖼️ Graphic Design

What I love about this graphic is how it deals with the problem of defining what an urban area is as part of the graphic. Seems like there are a lot of big administrative cities in China, and a lot of big urban areas elsewhere in the world.

📚 Random things

These links are meant to make you think about the things that affect our world in transport, and not just think about transport itself. I hope that you enjoy them.

The Radical Politics of Star Trek (Tribune)

The dinosaurs didn’t rule (aeon)

Next slide, please: A brief history of the corporate presentation (MIT Technology Review)

The Crooked House was Britain’s wonkiest pub. Then it burned down (CNN)

How I enlisted The Archers in an environmental battle for the soul of our countryside (The Big Issue)

✍️ Your Feedback Is Essential

I want to make the calls to actions better. To do this, I need your feedback. Just fill in the 3 question survey form by clicking on the below button to provide me with quick feedback, that I can put into action. Thank you so much.